People tend to think of Phoenix as a sun-belt car centric city, and for the most part they are correct. While Arizona ranks fairly low in terms of miles driven per capita, biking and public transit are not widely used in the Phoenix area. As is the case in other sun belt places like Southern California and Texas, driving is the default way to get from point A to point B. However, this does not mean that the region has no bike trails, nor does it mean that the area cannot be explored by bicycle.

The bike trails are quite nice and not crowded at all. My visit to Phoenix came at probably the best time of year to bike around the city, in the middle of April, and I was commonly the only one on the trail.

There are also a good number of trails, all connecting most parts of Phoenix and the nearby suburbs.

The crown jewel of the trail system is the Arizona Canal Path, a trail nearly 70 miles in length connecting places as far apart as Glendale and Scottsdale.

The trail has a very unique feel. The canal is obviously not natural. Nothing about it feels free flowing like the rivers and creeks I am accustomed to seeing elsewhere. It was constructed in the late 19th century kind of as the towns around Phoenix were being settled and incorporated. They needed the water and the means to transport goods, which was then far more dependent on water then. Later, they built Arizona Falls to harness some power from the canal.

Still, none of this is what I typically envision when I think of riding a bicycle along a river and seeing a waterfall.

However, the ride is not without natural beauty. Mountains, cactus and palm tress emerge around every curve.

It’s such an interesting feeling. Little mini-mountains in the middle of a city with over 1.5 Million People. Natural beauty around every curve, but every curve was planned carefully by engineers. Some of us are so accustomed to thinking of natural experiences as being separate from human development. This is especially the case in places like New York and Chicago where our homes are surrounded by development but we travel a few hours to be away from that development in nature. However, here on all of the Phoenix area bike trails, there is both, right there in front of my eyes.

Along these trails, it is possible to visit a lot of the area attractions. From the kinds of places you’ll see in almost every major city.

To spring training facilities for baseball and softball alike.

To the college and professional sports stadiums.

While exploring, you also never know what kind of random attractions you’ll encounter. Right in the middle of town there is a castle, and just east of town there is this hole in a rock people like to hike into.

I even got to see Central Station under construction and the one light rail line downtown.

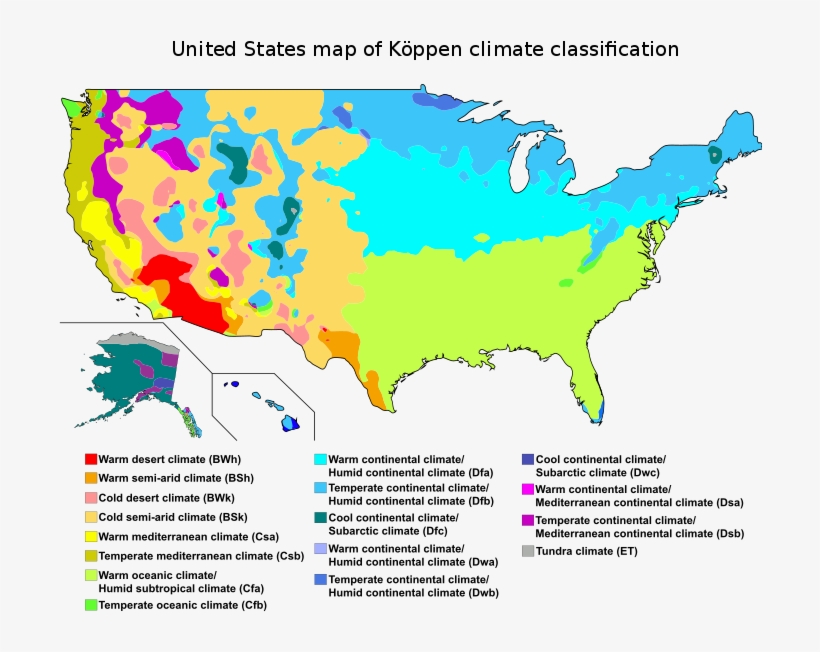

I also learned one other important lesson, the difference between cycling long distances in a semi-arid area like Denver and a full-blown desert like Phoenix.

In this part of Arizona, it was hard to drink enough water without even doing anything that involves physical exertion. Spending the whole day riding my bicycle felt like a constant search for water. I guess I now understand why the bike trails are empty and why they follow a series of waterways built to bring water into the area. It even facilitates some agriculture surprisingly close to the city center.

Still, there is nothing like the feeling of visiting so many tourist attractions traveling by bicycle on a day with sunshine and temperatures in the 80s (26-32° C).