Wyoming is not exactly “tornado alley”. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, the entire state averages only 12 tornadoes per year. Kansas, by comparison, receives eight times as many tornadoes each year despite being 15% smaller in area. Although a tornado in Southeastern Wyoming played a pivotal role in the VORTEX 2 project, Wyoming generally tends to be too dry for severe thunderstorms.

June 13th’s chase came up somewhat suddenly for me, based on a notification I had received about this outlook after being out of town, and not focused on the weather, the prior weekend. For some reason, before I even looked at anything else, weather models, discussions, etc., I had a feeling something major was going to happen.

This day somehow felt different, right from the start.

By 2 P.M., storm chasers were all over the roads, and at places like this Love’s Truck Stop in Cheyenne, Wyoming, watching the storms begin to form and trying to determine the best course of action.

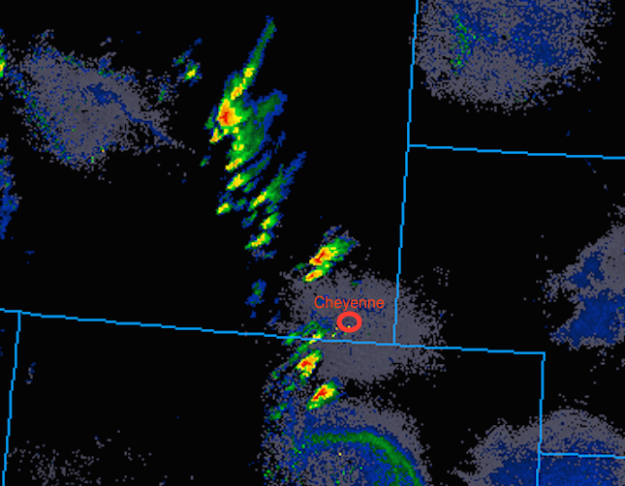

The decision we all were faced with was which set of storms to follow. The storms forming to the North were in the area previously outlined by the Storm Prediction Center as having the highest risk for the day, and in an area with great low-level rotation. But the storms to the South looked more impressive on RADAR.

Often, we need to continue to re-realize that the best course of action is to follow our instincts, and to follow them without hesitation or self-doubt. That is what I did, opting for the storms to the North.

It did’t feel like a typical day in Wyoming. Storm chasers everywhere. Highway signs were alerting motorists to the potential for tornadoes and large hail. Moisture could be smelled in the air. With a moderate breeze from the East South East, the atmosphere felt less like Wyoming and more like a typical chase day in “tornado alley”

When I caught up with the storms in Wheatland, Wyoming, hail larger than I had ever seen had already fallen. One of the good things about following a storm from behind is the ability to see hail after it has already fallen, as opposed to trying to avoid hail out of concern for safety and vehicular damage.

I stayed in Wheatland as long as possible, knowing the storm would head Northeast and I would have to leave Interstate 25. One of the disadvantages to chasing in Wyoming, as opposed to “tornado alley”, is the sparseness of the road network.

So I sat there for roughly 20 minutes. Looking at the storm, it felt like something was going to happen. All the necessary conditions were there, and the appearance and movement of the storm felt reminiscent of other situations which had spawned tornadoes.

I took a chance, using roads I had never traveled before, hoping the roads I was following would remain paved so I could follow the storm North and East.

There was a half hour time period where I had become quite frightened. I could feel the adrenaline rush through my body as the clouds circled around in a threatening manner less than half a mile in front of me. I lacked the confidence that the road would remain paved, or that I would have a reliable “out plan” if a tornado were to form this close.

After lucking out with around 10 miles of pavement, I suddenly found myself driving over wet dirt, and, at 20-30 miles per hour, gradually falling behind.

Luckily, I once again found pavement, drove by some of the natural features that makes Wyoming a more interesting place to drive through than most of “tornado alley”, and once again encountered large hail that I felt the need to stop and pick up.

Almost an hour later, and significantly farther north along highway 85, I finally caught up to the storm, just as it had dropped it’s first, and brief, tornado. And, this time, I was a comfortable distance from the thing! Unfortunately, this tornado would lift off the ground in only a few minutes.

Not too long after, I received notification that other chasers, following the storms that had formed farther South, had seen a much more impressive tornado, closer up, and had gotten better photos (the above is not my photo).

It was a strange day. Not only because Wyoming is not the typical place to see tornadoes. It also felt strange, as I had managed to do something impressive, yet still had reason to feel like a failure.

Most storm chasing is not like it is portrayed in the movies, with people getting close to storms all the time and getting in trouble. Most days, chasers do not see one. Seeing a tornado one day out of five is a very good track record for storm chasers.

Going out on a chase and seeing a tornado of any kind is impressive. Yet, to be truly happy with my accomplishment, I had to accept the fact that there was something better out there- something I did miss out on. This is a struggle we all face, in common life situations such as jobs, relationships, events, houses, etc. We often know we have done well, but always have this idea of something that is even better out there. Knowing this can make us indecisive, which will often leave us with nothing. In the age of text messaging and social media, evidence of such options has become extremely abundant, and quite hard to escape.

In a connected world, in order to be happy with ourselves, we need to find a way to both believe in ourselves, but also be accepting of the fact that someone else, somewhere out there, has done better. For that will always be the case, and we now have instant access to that knowledge. We cannot let knowledge of someone else’s more impressive accomplishments dampen our enthusiasm for our own. Otherwise, we will likely never be content.